Brexit is Real

As many interested Americans, I stayed awake through the night watching (rather reading live blogs because U.S. coverage was minimal until the vote ended – they were too focussed on Trump and Hillary bickering to notice) what was happening with the British referendum on whether to leave the European Union (EU). The BBC and other UK news outlets called the vote at around 5:00 AM BST (about 12:00 AM in the U.S.). The vote shocked many observers – the UK voted to leave the EU. This is an historic moment in time for international politics, international political economy, integration politics, and countless theoretical perspectives within many of these subfields. It will also have a drastic affect – at least in the short-term – for global markets.

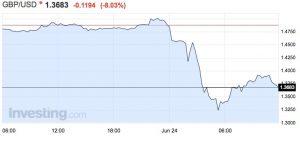

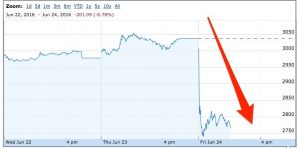

The fallout came fast. During the night the the pound dropped about 10% against the dollar, although as it stands now the drop is about 8% from before the vote. Asian markets took a hit, the U.S. market reacted as with a downturn, and European stocks are dropping. The charts below from Business Insider capture the initial fallout nicely. There is no doubt that Brexit will have consequences. Prime Minister David Cameron has already resigned. The UK will need a government that supported a “Leave” vote going in to the negotiations. Once they invoke Article 50 of the Treaty on the European Union, the UK will have two years to negotiate their exit. They will also need to negotiate new trade deals with every country where EU trade treaties once dictated trade. The web has exploded with stories, blogs, and news articles, most them explicating all the negative consequences of Brexit. I want to take a different path here. Something very few scholars and pundits are talking about is the consequences for EU integration post-Brexit. There is reason to believe that a UK exit will have positive consequences for integration, as the UK was often the thorn in the side of further progress.

Brexit, a Symptom of a Greater Disease

Brexit, a Symptom of a Greater Disease

The EU has been in crisis for a while now. The refugee crisis in Syria and surrounding countries only exacerbated the economic turmoil that already existed. The EU is plagued by the structure of the Euro – they have a central monetary policy, without the necessary fiscal and political structures in place. Nations on the Euro must rely on the European Central Bank for monetary control and the ECB is historically based on the German Bundesbank model, focusing on inflation rather than growth. This means that struggling countries, that want to spark their economy, cannot simply lower interest rates unilaterally. It also means that struggling countries cannot devalue their currency against world trading partners in order to get a favorable balance of trade. So they use the only course of action available, fiscal spending and debt. Even worse, for countries like Greece and Cyprus with a large segment of the economy relying of tourism, a strong Euro leaves them with an expensive destination that tourists ignore in favor of cheaper locations. Add the refugee crisis to the mix and we have a crisis. Greece began to become overwhelmed with Syrian refugees, the greater EU nations were hesitant to take them in, Turkey stepped in to help significantly, and this exacerbated the issue. These problems are structural and are not going away anytime soon.

The EU has been in crisis for a while now. The refugee crisis in Syria and surrounding countries only exacerbated the economic turmoil that already existed. The EU is plagued by the structure of the Euro – they have a central monetary policy, without the necessary fiscal and political structures in place. Nations on the Euro must rely on the European Central Bank for monetary control and the ECB is historically based on the German Bundesbank model, focusing on inflation rather than growth. This means that struggling countries, that want to spark their economy, cannot simply lower interest rates unilaterally. It also means that struggling countries cannot devalue their currency against world trading partners in order to get a favorable balance of trade. So they use the only course of action available, fiscal spending and debt. Even worse, for countries like Greece and Cyprus with a large segment of the economy relying of tourism, a strong Euro leaves them with an expensive destination that tourists ignore in favor of cheaper locations. Add the refugee crisis to the mix and we have a crisis. Greece began to become overwhelmed with Syrian refugees, the greater EU nations were hesitant to take them in, Turkey stepped in to help significantly, and this exacerbated the issue. These problems are structural and are not going away anytime soon.

The UK’s situation is different, but related, to the above problems. The UK has always has a special relationship with the EU. France – under de Gaulle – blocked UK entrance into what was then the European Community for a long time, citing sovereignty issues. Essentially, France was worried it would lose some of it power within the community if the UK joined, and because the UK has a special relationship with the U.S., there was belief that the U.S. would have some control over the Community. But Britain was persistent, de Gaulle left office, and the UK joined after a favorable referendum. Initially, even Margaret Thatcher was pro-Europe, as the picture to the left shows here wearing the infamous sweater with European flags in support of the Community. However, that didn’t last. She would eventually become against greater Europe and nationalist sentiment would continue to grow. At the core of Brexit is the rise of the far-right – which does not seem to be isolated to the UK. The UK Independence Party (UKIP) was a driving force in Brexit and the split in the Conservatives pushed Cameron to call for this vote to get reelected Prime Minister – it was clearly a mistake for his political career. The campaign for the Leave camp focused on migrant workers, immigration, and the (remote) “threat” of Turkish accession. Turkish accession is very far away and the Cyprus delegation is far from allowing for the Chapters of Accession to be reopened. But they played on these fears, exacerbated by recent events in Syria, and used the guise of nationalism and sovereignty to drive the Leave camp to a win. The Remain camp tried the fear route too, warning of great economic damage to the UK if they left, but rarely focused on the benefits of being in the EU. Even though the UK received a pretty good renegotiation deal, the politics of the situation were ripe for the Leave vote.

The UK’s situation is different, but related, to the above problems. The UK has always has a special relationship with the EU. France – under de Gaulle – blocked UK entrance into what was then the European Community for a long time, citing sovereignty issues. Essentially, France was worried it would lose some of it power within the community if the UK joined, and because the UK has a special relationship with the U.S., there was belief that the U.S. would have some control over the Community. But Britain was persistent, de Gaulle left office, and the UK joined after a favorable referendum. Initially, even Margaret Thatcher was pro-Europe, as the picture to the left shows here wearing the infamous sweater with European flags in support of the Community. However, that didn’t last. She would eventually become against greater Europe and nationalist sentiment would continue to grow. At the core of Brexit is the rise of the far-right – which does not seem to be isolated to the UK. The UK Independence Party (UKIP) was a driving force in Brexit and the split in the Conservatives pushed Cameron to call for this vote to get reelected Prime Minister – it was clearly a mistake for his political career. The campaign for the Leave camp focused on migrant workers, immigration, and the (remote) “threat” of Turkish accession. Turkish accession is very far away and the Cyprus delegation is far from allowing for the Chapters of Accession to be reopened. But they played on these fears, exacerbated by recent events in Syria, and used the guise of nationalism and sovereignty to drive the Leave camp to a win. The Remain camp tried the fear route too, warning of great economic damage to the UK if they left, but rarely focused on the benefits of being in the EU. Even though the UK received a pretty good renegotiation deal, the politics of the situation were ripe for the Leave vote.

The fallout includes many threats for a domino effect as Italy and others start to talk about leaving the EU and holding referenda. Countries all across Europe have Euroskeptic parties and these parties actually won many seats in the European Parliament – although, these votes tend to be cyclical because EP votes are held in off election years when out-parties have a greater chance of being elected. Regardless, there is a strong anti-EU movement in Europe.

But I disagree that this will lead to a domino effect and to the disintegration of the EU. I am hesitant to predict a stronger EU rising from the ashes of Brexit, but I do think there is an argument to be made that EU integration will progress further after the UK exit is finished.

Brexit Good for Europe?

The UK has been an obstacle to further EU integration for some time. They had enormous voting power under the new Qualified Majority Voting rules, which requires a double majority – 15 out of 28 (55%) member states plus at least 65% of the total EU population for an affirmative vote in the Council of Ministers. The UK makes up about 13% of the total EU population, giving their vote a lot of weight – third after Germany and France, respectively. The UK was a sovereignty protector in the EU. They often derailed additional attempts at further integration or opted-out of EU actions to preserve their position in global politics. In fact, I would argue that UK sovereignty was not (severely) threatened by being a part of the EU because of the opt-out mechanism basically created for the UK. The UK opted-out of the Schengen area (not a surprise here), the EU Charter of Fundamental Human Rights, the Area of Freedom, and Security and Justice. The EU was was quick to give the UK what they wanted because the UK paid about 12.57% of the total EU budget, just under Germany and France, respectively (2015 statistics). This meant that the UK had leverage in almost everything the EU did, while also opting out of the things they disliked. They were able to mold EU policy and integration, without actually abiding by the things they felt threatened their sovereignty. This can happen no more and their leverage is minimal at best.

Moving ahead, Europe is now free from the obstacle of the UK. France and Germany, among others, have been pro-integration for a long time. Yes, there are nationalist parties that want to leave. Yes, there are Euroskeptics, but the political climate is different in these countries. France and Germany, along with Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands started what is now the EU. France has been dedicated to further integration and Germany has shown the desire to keep the Eurozone together by its acceptance of recent bailouts in Greece and Cyprus. When the smoke clears and the exit negations are finished, the EU will go on with business as usual. Other EU countries will see the consequences of leaving – economic and geopolitical – and will refrain from exiting in quick fashion. Moreover, the consequences of a nation using the Euro leaving will be much more drastic than that of Brexit – without the Euro in play. Even so, having Italy, Spain, Greece, and other struggling Southern European nations leave may not be a bad thing (aside form the economic fallout) for Europe. These countries – combined with a central monetary policy without a central fiscal policy – are the primary reason for Europe’s economic woes. But again, this is unlikely to happen, and if there is a domino effect of exits, I do not think the EU can withstand the fallout. That being said, assuming the EU stays together post-Brexit, further integration may be the result.

This situation fits well with Liberal Intergovernmentalism, where the nation-state is at the center of further EU integration. Unlike Neofunctionalism and its arguments that spillover (functional and political) will lead to a spiral of integration, Liberal Intergovernmentalism argues that the process is much more reliant on national interests, changing (geo)political climates, and the ongoing bargain between nations in the intergovernmental organization. Thus, integration is not irreversible, but depends on the bargaining process and the interests of the member states – each member’s bargaining leverage based on their relative power. In the context of the EU, the UK had enormous bargaining power and used it to stifle integration, citing the fear of lost sovereignty and economic and political consequences. But now, the bargaining process will happen without the UK. If the current member states behave as they have in the past, more – not less – integration is likely. The interests of the regime that is left after Brexit converge on a set of shared interests – mainly economic but also geopolitical. “An international regime can be viewed as a set of implicit and explicit principles, norms, rules, and procedures around which actors’ expectations converge in a particular issue-area.” These norms, rules, and procedures are not just going to disappear post-Brexit. In fact, I would argue that issue and expectation convergence around EU integration will be strengthened without the UK. The path forward for the EU, according to Europe 2020 is as follows:

“The European Union has been working hard to move decisively beyond the crisis and create the conditions for a more competitive economy with higher employment.

The Europe 2020 strategy is about delivering growth that is: smart, through more effective investments in education, research and innovation; sustainable, thanks to a decisive move towards a low-carbon economy; and inclusive, with a strong emphasis on job creation and poverty reduction. The strategy is focused on five ambitious goals in the areas of employment, innovation, education, poverty reduction and climate/energy.

To ensure that the Europe 2020 strategy delivers, a strong and effective system of economic governance has been set up to coordinate policy actions between the EU and national levels.”

The last portion is most important. The Stability and Growth Pact’s rules need to be strengthened and surveillance needs to be more intrusive – yes, leading to more sovereignty lost. But this is the way forward for a Supranational and Federal Europe. Without the UK, these items may be easier to tackle and France and Germany will most definitely be able to control the agenda in the coming years.

Now of course, severe problems exist. The monetary union is not sustainable without a fiscal equivalent. Struggling countries turn to government spending to increase growth because they lack monetary options. This leads to debt crises and then bailouts. This is unsustainable. The Eurozone cannot be sustained in the long-term in this way. But only further integration and further erosion of sovereignty can solve this problem. More, not less, integration is required to solve these deep structural problems. Given that the UK will not be involved in these negotiations, it may be possible to move forward with integration to solve some of these issues. Many scholars in the recent past began to seriously focus on the Federalism perspective, treating Europe more and more like a nation-state. Of course, Brexit falls in the face of this paradigm (although secession from nation-states is not unheard of). But when one looks at the institutions of the EU, one cannot help but see what appears to be a federal government. The EU has an Executive in the Commission, a bicameral legislature with the Council of Ministers and European Parliament (both with voting power), and the European Court of Justice, which has independent power and has ruled EU law to be supreme. It has a vast committee system, a giant bureaucracy (sometimes blamed for creating a regulatory state), and is governed by an extreme system of multi-tiered pluralism (with lobbying happening at both the supranational and member state levels). Brexit will give the remaining powers more leverage in negotiation with the UK and even more leverage with controlling the EU’s future toward integration. The interesting thing for the UK is that not much is likely to change in terms of the EU policies they dislike! In fact, they may get a worse deal.

Brexit’s Failure

The UK will have to negotiate an exit with the EU, which will include a trade deal. To trade with the EU, a nation has to follow its rules (even non-members). The UK may be subject to the same tariff and non-tariff barriers that the U.S. faces when trading with the EU. UK farmers will lose the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) benefits and the payments that come with that benefit. EU regional funding will disappear from the UK. The UK will have to negotiate new trade deals with about 50 countries where the EU’s treaties were in place, and they have to do this without the leverage of the EU common market with over 500 million consumers. Moreover, to trade with the EU, a nation still has to follow their regulations. In fact, one of the biggest benefits of the EU is a single regulatory policy, making trade with all EU nations easier than having 28 (now 27) different national regulations. Multinational firms appreciate one regulatory policy rather than 28. The EU will be firm on the negotiation to set a precedent for other countries wanting to leave. Plus, since the World Trade Organization (WTO) regulates trade with its members (including the U.S., EU, and China), and the Most Favored Nation (MFN) principle requires that all members of the WTO get equivalent deals on most everything, the UK isn’t likely to get better trade deals outside of the EU, as many in the Leave camp suggested.

But worst of all, the UK will have no leverage in where the EU goes from here. No voting power. No budgetary power. They will watch from the sidelines as greater Europe moves forward with the largest market in the world. Interestingly, this is exactly why they wanted to join in the first place, so they could have a say in Europe, protect the nation from getting left behind, and take advantage of the benefits from vast transaction cost elimination.

In the meantime we will see how Europe moves forward. There will be struggles. There may even be more exits (I doubt it, but as nationalism and far-right parties grow, it is not impossible). But in the end, without the UK, greater integration is possible. If the interests of the member states converge, further progress can be made and possibly lead to a more Federal Europe – maybe it will even have a common fiscal policy. Don’t hold your breath though, these are possible long-term pathways. For now, the short-term consequences of Brexit will be powerful and deeply felt by many economies around the world.